Interview:

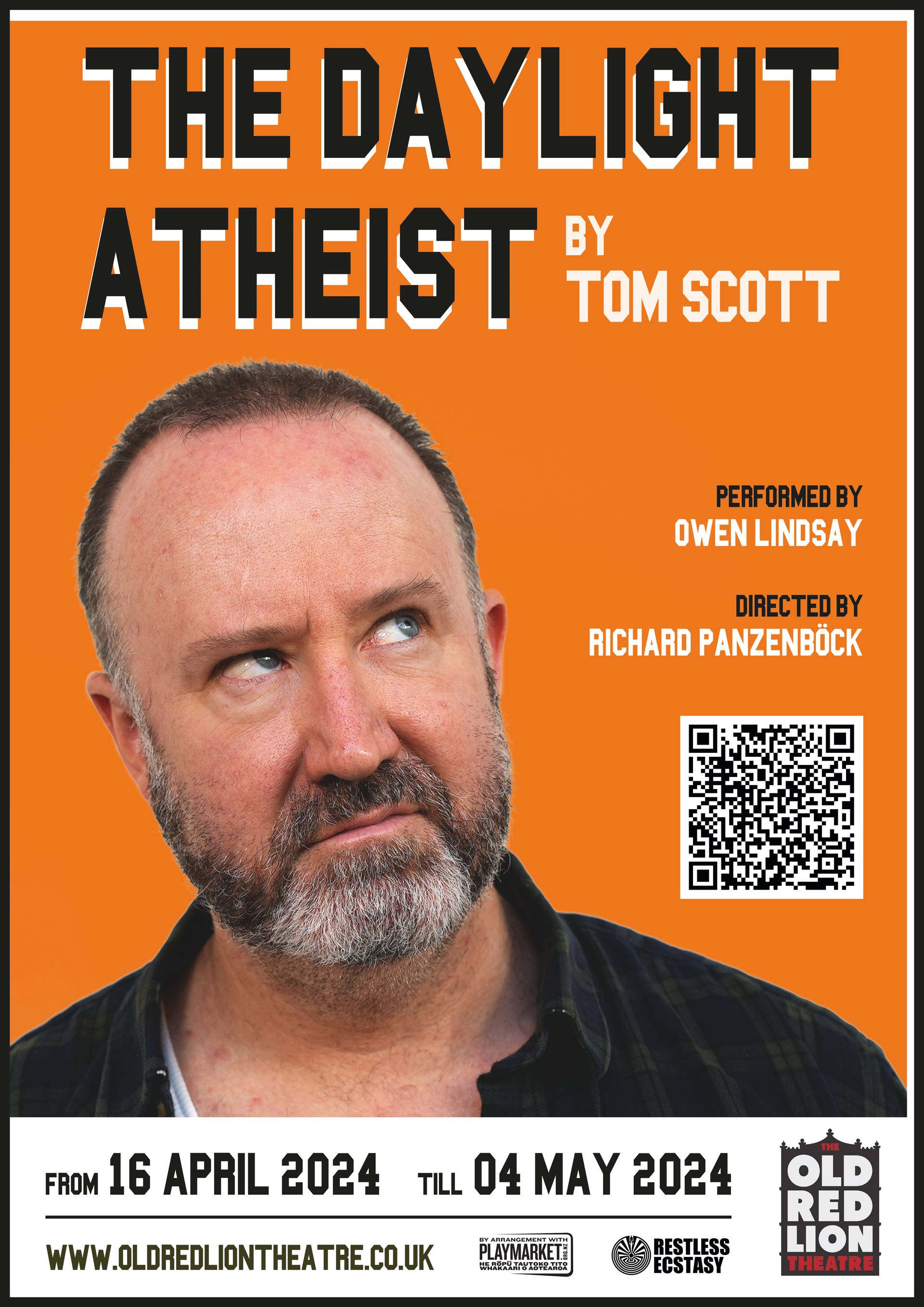

OWEN LINDSAY on THE DAYLIGHT ATHEIST at OLD RED LION 16 Apr – 4 May

Written by award-winning satirist and author Tom Scott, THE DAYLIGHT ATHEIST, was an instant hit when it premiered in New Zealand 2002. The multi-talented OWEN LINDSAY is bringing this one man play to London with himself in the title role. There are some nice parallels as Owen is also an Irish emigrant to New Zealand, which is exactly the dynamic the show explores. We’re pleased to put some questions to Owen to find out more.

LPT: It’s wonderful to have found a play that seems to have been written for you. When did you first come across it and what was your initial response?

I was fortunate to see the play when it received its world premiere in New Zealand back in 2002, in a production by Auckland theatre Company, and starring a brilliant local actor named Stuart Devenie. It struck a chord back then, since the story of an Irish emigrant family was close in many ways to my own. I was really only beginning my journey as an actor at the time, and I guess it sort of became a personal Everest for me. The desire to showcase it became even stronger when I moved back to Ireland in 2005, but it would still be along time before I would feel ready to climb the proverbial mountian.

LPT: Please could you tell us a little bit about the story of the play.

It’s a very intimate piece, loosely based on the life of the playwright´s own father. Essentially it’s a portrait of late-life male alienation, of a man disconnected from those closest to him and spending his days reliving past exploits. It´s a theme that recurrs frequently in many Irish and Irish-themed plays, like Enda Walsh´s “The Walworth Farce”, or Conor MacPherson´s “The Weir”, where stories and how they are told become an expression of identity. In our story, the protagonist Danny Moffat grows up in semi-rural Ulster, having been sent away to live with a widowed Aunt at a young age, and struggles to form close attachments throughout his life. He moves to New Zealand after serving in WW2, bringing with him the wife and child he acquired by mistake while on leave. They wind up living in the rural New Zealand of the 1950´s, struggling with culture shock, poverty, alcoholism and their own dysfunctional family dynamic, along with Dan´s many unquiet demons and the family´s buried secrets. Along the way we´re introduced to Dan´s Maori best friend, his son´s fickle headmaster, a rogues gallery of funny, coarse and eccentric personalities from all the different walks of Dan´s varied life, and are invited into a sensitive exploration of his loneliness, habitual self-sabotage and unfulfilled need for love.

LPT: Were there particular scenes that really resonated with you?

Tom Scott, the playwright, is a celebrated Kiwi humorist in both print and on film and TV, so his depictions of local eccentricities and New Zealand cultural mores are all very fun to portray. I suppose there´s probably something in having grown up an immigrant that gives you a slight outsider´s perspective on the place you call home, which I find resonates quite strongly with me; there´s always a knowledge that you come from somewhere else, even though this place might be all you´ve ever known, so there´s a part of you that´s somehow always on the outer. In the play, we see New Zealand very much from Dan´s often-perplexed and dryly amused new comer´s point of view, which I can absolutely relate to.

LPT: The character you’re playing is described as a highly engaging, bad-tempered, affable and utterly irrepressible raconteur. He’s the (not entirely reliable) guide and narrator. Have you met someone like this in real life and do you ever find it helpful to base your characterizations on real people?

Oh absolutely. I´ve been fortunate to live in all of the places where the action of the play is set (more or less); at different times I´ve lived in Ireland, New Zealand, Germany and the UK, and all of those experiences have helped me to understand the character better. When I lived in Ireland, and when I visit still, I realize how close Dan is to so many Irish men, particularly of an older generation: the difficulty in expressing personal feelings except via outbursts of vituperative fury, the habitual alcoholism, the devilish sense of humour, the love of talk and long-winded storytelling, the almost toddler-esque levels of emotional caprice… I would see that almost daily, and it definitely has helped inform my portrayal. So while I wouldn´t say there´s any one model for Dan out there, you could say he´s a child of many fathers.

LPT: What about the themes of the play, what do you particularly want to share with the audience?

I think the play is about many things: the loss of emotional moorings at a young age, and the fallout into adult life are particularly prominent, as is the struggle with an under developed capacity to process complex emotions, resulting in abusive and self-destructive behaviours. Overall though I think it´s about developing a sense of empathy for someone who is not, on first impressions, terribly sympathetic. I suppose I´d like people to come away with a reminder that we´re all products of our own emotional and psychological experiences, and that those can scar us in ways that we ourselves don´t even understand, or know how to contextualize. In these super polarized times, when even slight disagreement can seem to provoke responses of extreme hostility, I think it can pay to remember that we´re all just human, all of us flawed and vulnerable, and deserving of compassion.

LPT: We’re impressed to see that as well as actor, you’re also director and fight choreographer. For this show you’re working with award-winning European director Richard Panzenböck. As follow directors do you have a similar style?

Richard and I are quite different in our approaches I would say. Without wanting to speak too much for him, I think his background in Austrian theatre gives him a very compositional perspective, seeing the play in terms of visual and aesthetic qualities, rhythms and crescendos, as well as vividly creating the world which the actors inhabit. When I work as director, I´m very much driven by attention to the actors performances: those who work for me know me as a hard task-master, but one that can bring out their best work, sometimes stuff they didn´t know they had. The finest compliment I ever received was from an actress I worked with in Dublin: she told me that before the production she was terrified of the role, but that after playing it for me, she wasn´t afraid of any role anymore. From a design and aesthetic point of view, though, I will confess I´m much less detailed than Richard is, and paint the visual and environmental world of a play in much broader strokes. As a combination I do think we´ve complimented each other quite well on this project; his attention to the physical environment has enhanced my pursuit of the performance to find a fuller and more detailed expression.

LPT: We’ve heard that one-man plays are particularly scary for actors and we wondered whether this holds true for you. What could possibly be scary about a solo show?

Forgetting the lines. In an ensemble production, if you go dry there are other people there, who can at least potentially save you. When it´s just you, you´re really on your own if that happens. At the outset of this process I wasn´t even sure I´d be able to learn the whole text, but it´s been surprisingly a lot less difficult to remember than I´d feared. It helps when the writing is so good, since it has it´s own rhythm and musicality. That all changes when there´s people watching though. The other aspect that can be a bit intimidating is, there´s really nowhere to hide. Even when you have a leading role in a larger-cast play, you´re rarely always onstage- you get your time to breath and other people take the spotlight, so if you´re having an off night (we all do sometimes) you can reset a bit before you go back on. In a solo, you just have to keep going, and any reset you do will have to take place in front of the paying public.

LPT: Without giving too much away, could you tell us about your favourite scene and what you love about it.

It´s hard to pick a favorite honestly. The scene where Dan takes (admittedly petty) revenge on the local schoolmaster for a litany of clumsy abuses and slights is a comic highlight, and conjures up many a memory of foolish and mirthful mischief in my own youth.

LPT: We’re intrigued with the name of your production company, RESTLESS ECSTASY.

It’s a quote from MacBeth, please could you tell us more about this. I´ve been shaped by Shakespeare since I was a student, and Macbeth is a favorite role. In later years I became influenced by European avant-garde theatre traditions and physical theatre, and by a certain genre of Polish experimental theatre very much engaged in the pursuit of a kind of raw, ecstatic performance closer to a species of ritual than to formal acting. After I moved to Dublin, one of the companies whose work I greatly admired was Rough Magic, who likewise drew their name from the work of the Bard. So when it came time to found my own company, I was searching for something that would connote the kind of mobile, muscular and energetic work I was interested in promoting, and I came back to Macbeth´s private quasi-confession: “Better be with the dead, / Whom we to gain our peace have sent to peace, / Than on the torture of the mind to lie / In restless ecstasy.” It conjured up a kind of all-or-nothing, do-or-die spirit that I felt was appropriate.

LPT: Finally, in premiering this play over here, how do you think London audiences will respond to the humour?

Well, I hope positively. A joke is a joke, whichever accent its delivered in. There´s no doubt that the play has aged in the 22 years since its premiere, so some of the jokes may come off a little saltier than might be considered PC nowadays, and the specific character of New Zealand humour- often bone dry, and innately self-deprecating- may be a bit new to London audiences. But, hopefully, people should see it in the light of a historical context, rather than a contemporary expression, and experience the laughter along with the tears in what is a varied, challenging and wholly worthwhile evening´s theatre.

THE DAYLIGHT ATHEIST

The UK Premiere of a hit New Zealand Classic Old Red Lion Theatre, Islington 16 April– 4 May 2024