We all know the scene.

An actor steps forward in a quiet darkness, all poise and purpose, to speak of horror, beauty, truth, lies. Beneath a spotlight, before a waiting audience, they will reach into themselves and deliver the moment that will bring tears, break hearts, and be on everyone’s lips long after the curtain falls. They open their mouth. Then a phone rings.

Disruption of live performance is not new. While the telephone has been an occupational hazard for drama since it became pocket-sized, there are plenty of other ways that people can cause problems for actors and audiences. The theatre is a public space after all, and where the public congregate, expect to find a variety of behaviour – some reasonable, some not.

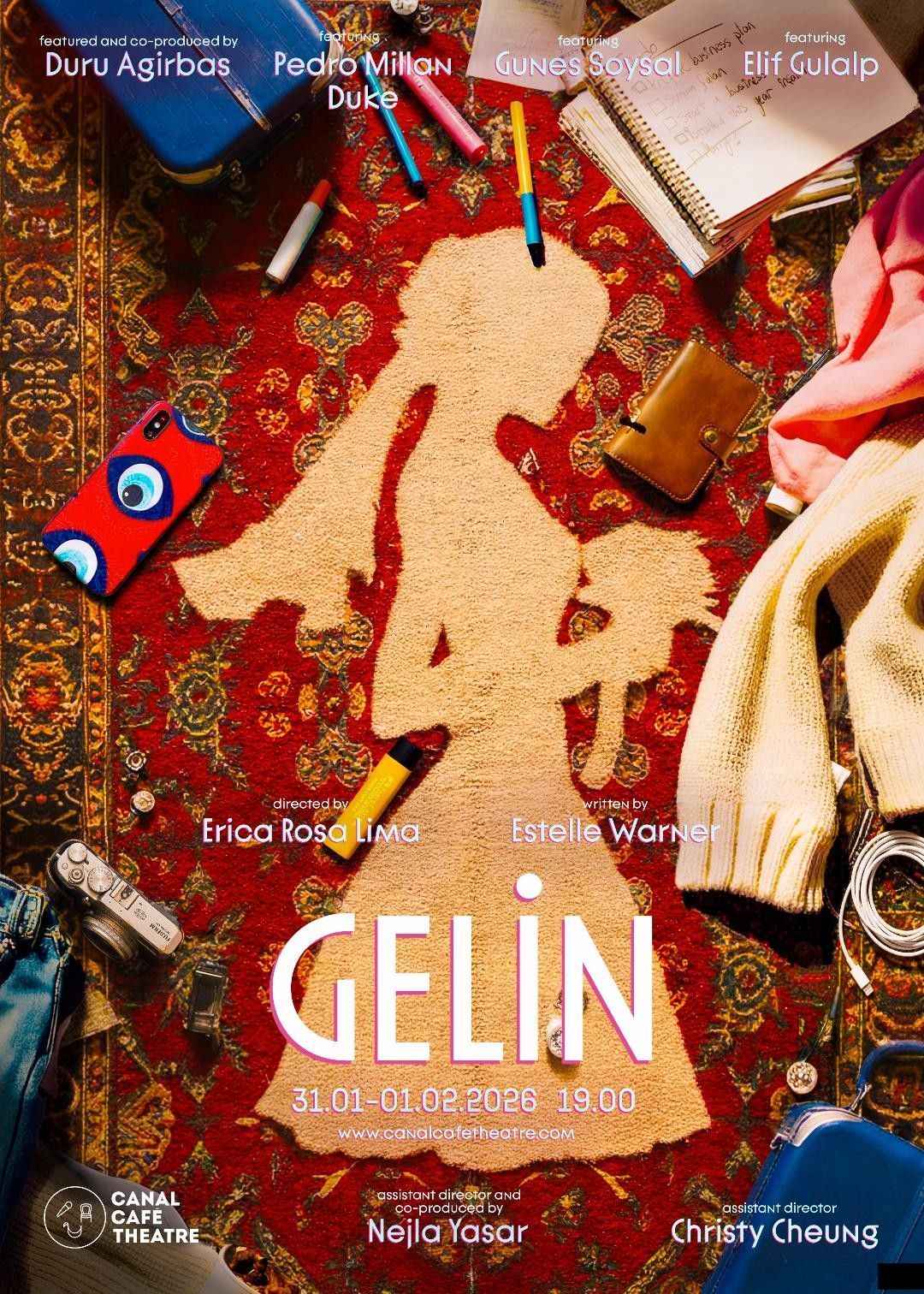

For the wary attendee, pub theatres can be particularly perilous. Any disruption, from ringing phones to talking to drunkenness, are likely to have an even greater impact if they occur in small rooms which, in some cases, only seat a few dozen people. Cheap tickets, easy access to booze, and a lack of ushers can make for an electric atmosphere, but an uncertain one, and performances can just as easily be ruined as they are enhanced.

Of course, part of the thrill of watching live performance on the fringe comes from the feeling that anything can happen. The tension becomes even more heightened in small spaces, and while we may begrudge the whispers and jingles, we need the company of others to get a fulfilling experience. Besides, there is no historical precedent for passive audience behaviour.

No Rulebook for Behaviour

The expectation that theatre audiences should be seated, silent, and clap at appropriate times, is relatively recent. Shakespeare was popular entertainment during the Elizabethan era, which meant that his audiences could be rowdy, drunk, and inclined to the sort of behaviour that would be unimaginable today. Audience researcher Dr Kirsty Sedgman attributes this change to a ‘deliberate, coordinated campaign’ undertaken by elites who, fearing an influx of lower-class and racial others during the 19th Century, wished to exclude such undesirables from their spaces.

The campaign was successful. The raucous atmosphere of lively crowds was replaced with respectable silence, and the theatre, which had for so long been a space open to the public, came to be dominated by the upper class. Such disparity continues to this day, and in 2015 a report from the Warwick Commission found that the wealthiest, best-educated, and least ethnically diverse 8% of the population accounted for nearly a third (28%) of attendance to theatre.

We should be careful when considering questions of behaviour. Given the history of theatre, and a lack of income and ethnic diversity at the top, it is easy to imagine a situation where rules could be abused. Theatre is already prohibitively expensive without people using poorly-defined rhetoric to exclude others for how they look and sound, and this is true for all venues, regardless of size.

A Little Respect

Theatre should be open, but it should also be enjoyable. Allowing all behaviour would hardly be fair on paying audiences, nor indeed performers, who put heart, soul, and sweat into their shows. Take a recent horror story from Jake W. Francis, whose high-intensity, one-man show at the Edinburgh Fringe was disrupted by drunken chatter, ringing phones, filming, spillages, and one audience member even crossing the stage to leave the venue. In this example, some of the audience acted without respect for Jake, or each other, and spoiled the show.

“I like to think that theatre etiquette is a mutual contract between actor and audience,” Jake said, “they both put aside distractions for a couple of hours and experience something together.” When asked how disruptive incidents could be avoided, he put the onus on venues and their patrons. “I don’t think it should be down to the performers to enforce etiquette,” Jake said, “it is up to the theatres to remind audience members of proper behaviour in a performance (no talking or phones) [and] for the audience members to hold up their end of the theatrical bargain.”

Down with the Sickness

Theatre can be provocative, particularly on the fringe. Without the pressure of satisfying substantial overheads, national critics, and large audiences, these small spaces can take risks and experiment, bust taboos, explore difficult topics, and challenge tastes. In this way, a pub theatre can be a testing ground for extreme material and provide a more intense experience than one might get elsewhere. But if these plays are meant to be shocking, can we really blame audiences for being shocked?

Despite being a seasoned theatre-goer, playwright and critic Siân Rowland was recently stirred by a particularly violent scene. She explained the necessity for theatres to warn about upsetting material, as this way “there’s a little part of you that’s prepared, it’s almost like covering yourself.” While it is important that theatre remains free to express difficult topics, proprietors and productions can avoid causing offence with warnings. Audience members can enjoy themselves, knowing full well the kind of show that they will be watching.

Pub theatres have begun to offer content warnings for their shows. The Brockley Jack give people the option of finding out about a show’s content beforehand. As Artistic Director Kate Bannister explains, this approach “balances the need for the audience to make an informed choice whilst also not giving away too much.” Katy Danbury, Artistic Director of the Old Red Lion, also recognises the need for audiences to be made aware of extreme content, asking “companies performing at the ORL to advise us” because “you never know who is coming through your doors.”

Open to All

If we want theatre to be truly welcoming, we need to acknowledge that audiences have diverse needs. Not everyone will be able to adhere by the rules we set, and for entirely valid reasons. Theatre 503 has countered this problem by introducing relaxed performances. Every major run has a matinee for parents and babies, as well as a show where house lights are left on and doors are kept open, so that attendees can come and go should they feel anxious.

In this way, the theatre is not only able to widen their audience but influence other venues and creatives to follow suit. “It’s important for us as a theatre and as an industry to be responding to the needs of our audience members,” producer Jake Orr states, “if we can instil this in creative teams at an early level that will help them in the future when thinking about accessibility.”

Pub theatres like Theatre 503 are in a unique position to influence change. By being situated as they are, these spaces can exist within and serve communities, providing low-cost and accessible entertainment for local people across all backgrounds and abilities. The pub theatre can bring people together to have a drink, see a show, and let their hair down. As the year draws to a close, another uniquely British institution serves a similar purpose.

Audience as Performers

Audience behaviour can be disruptive, but what if it was part of the act? As mentioned earlier, theatregoers were not always so restrained, and at one point in time were inclined and often expected to talk back. Whole shows could be organised around these interactions, not only entertaining audiences but involving them in the drama. One of the oldest, and most popular forms of this kind of theatre not only anticipates audience participation – it relies upon it.

Pantomime needs an active audience. Developed in England out of Mummer’s Plays and the Music Hall tradition, these theatre shows feature lewd gags, cross-dressing, and plenty of opportunities for audience members to respond from heckling and hissing to laughing and singing. A staple of the festive season, pantomimes are populist family entertainment that, if done well, can create a special bond between audience and performer that higher-brow fare can only dream of.

Far from being a nuisance, noisy audiences are ideal for the pantomime – provided they play along. Much like a comedy performance requires laughter, pantomimes require attendees to join in at the right moments, from booing the villain, cheering the hero, and calling out the storied warning of ages past, present, and future - he’s behind you! These elements make the pantomime ideal for small children who, far from having to sit still and be quiet, get to join in.

The feeling of participation, of effectively becoming a performer, can be truly joyous for not only the young but adult alike (who may also get a kick out of the odd dirty joke). As the nights get colder, we could all benefit from a bit of cheer at the theatre, and at this time of year a soap star in drag may well have more appeal than Shakespearean verse (apologies Will).

So how should theatre audiences behave?

From what we have seen, it depends entirely upon the theatre, the performance, and the audience themselves. But if there is to be one answer, I would argue that theatre is there to be enjoyed – with openness, respect, and most importantly of all, fun.

Just turn your phone off please.

@November 2018 London Pub Theatres Magazine Ltd

All Rights Reserved